-

Migratory Birds

Leann Beard

Living in Brooklyn, I have enjoyed getting to know the migratory birds that visit us each year, from the piping plovers of the Rockaways to the colorful warblers that visit The Vale to the little birds we only see in the wintertime, like the dark-eyed juncos in my courtyard. I had no idea a city could be host to so much wildlife.

Unfortunately, these birds have a very difficult time migrating through New York City. Birds typically migrate at night and while traveling at high speeds, they often collide with the glass windows of our many buildings and skyscrapers. The sunrise in New York City often reveals a night of carnage, with dozens of concussed or dead birds littering the sidewalks of all five boroughs.

Alongside the global decline of migratory birds and the particular situation of New York City, where building code dictates only new buildings need to have bird-friendly building and window design, the omnipresence of New York Police Department continues, in the subways, on street corners, and in helicopters in the sky.

My quilt square aims to highlight this bleak dichotomy, and contrast what is being lost with what is being protected. This comparison is not random; one of the many downfalls of living in a militarized police state are the choices made along the way of what we will not have. We will not have clean air or water; we will not have free, high-quality public transit; we will not have as many migratory birds visit as we did last year; and so on and so forth.

I hope that one day, when the sun rises over Manhattan on a beautiful spring day, the birds who passed through the night will not be underfoot but somewhere overhead, far, far, away.

-

Sierra Mixe

Gaura Coupal

Sierra Mixe is an indigenous corn found in Oaxaca, and it’s quite the marvel. Using careful growing and breeding techniques over thousands of years, the Ayuukjä’äy grow this corn, which fixes its own nitrogen from the air, by way of gel secreting, reddish, aerial roots. The corn does not need external fertilization, or very nutrient rich soil, in order to thrive. It also grows in colder, northern ecosystems.

There is so much wisdom and agricultural tech knowledge that industrialized countries can learn from indigenous people.

The Sierra Mixe region of Oaxaca is named for the people who live there (who call themselves the Ayuukjä’äy). Zapotecs, Aztecs, and Spanish conquistadors did not conquer them in the past. When peoples are conquered, culture is often decimated. It’s not “lost.” Agriculture is part of culture. Colonization and conquests have ramifications we don’t even know how to measure.

My quilt block is a visual invitation to look for creative techniques in growing food crops, be it in the traditions of the Ayuukjä’äy, in one’s kitchen container herb garden, community gardens, or large scale farming.

-

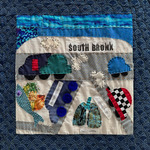

If You Breathe You Should Care

Carol Ann Daniel

Many years ago, I worked in the Mott Haven section of the South Bronx providing social services to underserved populations. This was at the height of the HIV crisis in New York and this area was particularly affected because of the high rates of drug use. The families mostly hailed from Latin America, the Caribbean and Africa. However, they all had one thing in common, asthma. Almost every family had a child or an adult with asthma. We sought to address the high rates of asthma by helping families to find housing that was free of roaches, rats and mold. And when that failed, we took their landlords to court to force them to make the necessary repairs. After I left the job, I maintained communication with some of the families and colleagues who touched my life and whose life I became a part of.

My quilt draws attention to the environmental injustice in the South Bronx. One of the things I learned in subsequent years was that asthma is not only caused by mold and vermin infestation but by environmental inequality. Your ability to breathe clean air should not be determined by your zip code, the color of your skin or your socio-economic status. The area referred to as “asthma alley” is the 3rd poorest in the city and is 97 percent Latino and Black.

According to New York City community health profiles, the South Bronx has the highest levels of PM2.5, the most harmful air pollutant - 10.0 micrograms per cubic meter compared with 8.6 citywide. Other sources of air pollution include the excessive amounts of diesel-intensive industries that serve other communities. The Fresh Direct warehouse, and the printing press of The Wall Street Journal are both located in the South Bronx. Hunts Point Food Distribution center, the largest in the country, is also part of the steady stream of truck traffic. Although the area is home to only 6.5 percent of the population of the city, the South Bronx has one third of the city’s waste treatment plants.

Other sources of pollution include the exhaust fumes from a network of highways. There are ten highways running through the Bronx and four of those surround the South Bronx. In contrast there are only two highways running along the outskirts of Manhattan. This pollution causes asthma and other respiratory illnesses, leading to health complications and premature deaths for residents of the South Bronx. The asthma rate in the South Bronx is so high it was nicknamed asthma alley. The Guardian reported that asthma hospitalizations in the South Bronx are five times the national average and at rates 21 times higher than other NYC neighborhoods. Not surprisingly, city data also suggest that this area was among hardest hit by the coronavirus. Research confirmed that air pollution is associated with COVID-19 death.

Every New Yorker has a right to the city including equitable use of the services and resources that the city has to offer, participation in the decision making of how space is utilized and the right to a habitat that is clean, safe and life affirming. To achieve these goals, we need more equitable environmental regulations that offer protection for all forms of life in ways that ensure a responsible relationship between individuals and nature and promote the dignity and humanity of individuals, families and communities.

-

Light as a Symbol in Many Cultures

Doris Douglas

As a workshop facilitator it is important to involve all participants in the process of engagement. The collage presented here reflects igniting lights that reflect the meanings and symbols of many cultures. The symbolism of lights goes back to pre-Judaic/Christian times. The winter solstice as well as the aurora borealis reflects hope and progress.

The lighting of candles within the Jewish celebration of Hanukkah reminds us of the perpetuity of good things to come. Other types of candle holders such as the kinara grew out of a need to bring people of African American heritage together in the concept of Harvest– not just the harvesting of crops, but the harvesting of good principles to be practiced throughout the year. The concept was developed by an African American scholar named Maulana Karenga. Of course we cannot forget the symbol of lights that symbolized the birth of Jesus Christ.

All of the materials used in making this collage are made of fabric. Some are actual fabric. Others are reproduced paper images which are transferred to fabric.

-

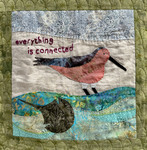

Everything Is Connected

Margaret Marcy Emerson

Our natural world is beautiful, complex, and deeply connected in ways we both understand and are yet to discover.

In this quilt block, I feature two creatures whose lives are inextricably connected.

The horseshoe crab has existed practically unchanged for nearly 450 million years. Yet these seemingly resilient creatures are presently in decline along our east coast and are now listed as vulnerable, putting their long term survival into question. They have suffered over harvesting for fishing bait and biomedical testing from the pharmaceutical industry due to a unique property in their blood and habitat loss.

The Red Knot, a sandpiper with an incredible migration route from the arctic tundra to the southern tip of South America, Africa and Australia, is dependent on the rich eggs of the horseshoe crab to sustain them on these long journeys. In a 2021 bird count in Delaware Bay on the Jersey coast, only 6,880 red knots were spotted, a fraction of the 90,000 birds counted at the same location in the 1980s.

Biodiversity underpins all life on our planet. Healthy communities rely on well-functioning ecosystems for clean air, fresh water, food security, health sciences, economic well being and livable climates; these vital interconnections are not always apparent or appreciated.

Respecting and protecting the natural order around us is essential for a sustainable future.

-

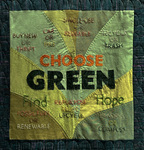

Finding Hope

Margaret Marcy Emerson

Climate change, habitat and biodiversity loss, and increasing social inequality have caused many of us, myself included, to feel a deepened sense of anxiety and despair. When our ecosystems are degraded and compromised, so are the health and livelihoods of our communities. By examining our individual actions on a daily basis, we can reduce our carbon footprint and make a positive impact on our city and planet. From the transportation choices we make, the food we eat, the goods we buy, the trash we create, the energy sources we utilize, to how we dispose of our unwanted goods — all of these decisions are in our power. Our choices matter.

In my quilt block, I embroidered questions that focus on ongoing choices I make in my everyday life. I’ve found that making consistent small choices lead to bigger, more impactful choices. Speaking up and getting our families, our neighbors, and our communities to join in taking action is one of the quickest and most effective ways to make a difference. Through these efforts over the past couple of years, I have expanded my community, and found hope.

Once we ourselves begin to make these choices, we can go on to urge our families, communities, political leaders, employers, and the businesses we all patronize to make green, sustainable choices wherever we can.

-

The Apocalyptic Fire

Angela Francis

The apocalyptic fire enshrouds the tree of life, flowers blooming, green fronds and white daisies peeking out from the dark. We see the fire but we also see light and bursts of life exploding near the branches of the tree. A pink heart throbs between a couple, walking toward the tree, hand in hand, their future uncertain, their names unknown. The tree and the people are in silhouette but everything else is alive, pushing the limits of endurance, striving to bloom.

(Written on behalf of Angie based on the images in her square, created in layers of orange and blue fabric, with the fire/light, the tree, the flowers, the heart, and the humans appliqued with orange thread. ~ Deborah Mutnick)

-

Capitalism Is Unsustainable

Andrew Hansen

Capitalism is inherently unsustainable. As long as capitalism is the world’s main economic system, accelerated climate change will never end. It’s almost inconceivable to think of a different way to make the world work, but, if we don’t find a new system, capitalism will ultimately destroy our planet. My quilt block shows a giant dollar sign being torn apart by natural forces. A negative interpretation of this quilt block is that all of humanity’s achievements will be worthless and forgotten once capitalism causes the extinction of the human race, but Mother Earth will continue on. A more positive interpretation is that humanity will create a new sustainable system of coexisting, and the relics of capitalism will simply dissolve into the natural world, just like the ruins of other past civilizations.

I intentionally chose to create my quilt block in a more “cutesy” style because I enjoy subverting a viewer’s expectations. I believe the message is absorbed more readily once the viewer realizes what looked like a typical sweet arts-and-craft project from afar actually expresses a much more complex and somewhat uncomfortable subject matter.

-

Make the Soil Rich

Sarah Hutt

The idea for this quilt came out of the idea of “making the soil rich.” This personal mantra grew out of a desire to find ways that I could effect positive change. With so many massive problems–environmental, economic, social–facing current and future generations, I often wonder what I can possibly do to help. I believe I can make the soil rich, put what I’ve learned from my elders, experiences, community, values, back into the soil for the next generation to grow strong. I can’t control the outcomes, but I can be dedicated to helping those I influence in my life and work, to grow strong, well, and wise by sharing what I know and have learned, and encouraging others to do the same.

As I started on this project, “making the soil rich” took on new meaning. I wondered, what would our societies look like if we poured our resources into our resources, into maintaining and developing them with purpose? What if in building our cities and space we prioritized building in balance with our environment and the essential resources we all depend on, rather than profit? How would those cities grow? How might they be more equitable, sustainable, and healthy? How might they make the soil rich for future generations? Rather than perpetuating a system where we aspire to make ourselves rich, what if we shifted to a world where we invest in making the soil rich to create abundance for all?

My quilted block explores this question.

I used primarily cotton material that I dyed naturally and eco printed with plants and homemade iron water made with rusted nails and horseshoes found in farmed soil and forests to tangibly bring the idea of the richness of the soil into the work.

-

We’re Not So Different, YOU & I

Allison Munson

I was very inspired by Braiding Sweetgrass, by Robin Wall Kimmerer, while working on my square. She made me want to take a look at my relation-ship to the earth and nature, and if I view these things as gifts, or prop-erty, or commodities, etc. The indigenous people in her book are resolute in viewing every aspect of nature as our peers, part of our community. Taking this mindset, of being kind and respectful to those around us, really resonates with me, that the earth is not just a helpless victim of our abuse, but a fellow neighbor that we are bullying and taking advantage of, not seeing how valuable it is to our daily lives.

In my square I want to highlight our similarities, and found some fun metaphors between our thumb prints and tree stumps, used for our identification, frozen in time. A bit of a stretch, I also love comparing leaves and handprints. I stared for a long time at my own hand, how the veins branch off and extend to the fingers, how the ends curl in when they’re tired or cold.

Akin to how we discuss human differences, through race, gender, religion, ability, etc., I wanted to show trees in our neighborhood as I would handprints in a Sunday School, showcasing how even when our skin looks different, or our cells are square or round, we get our energy from food or the sun, we are all welcome here, and we all should be treated equally.

-

Stardust: Toward a Revolutionary Urban Ecology

Deborah Mutnick

I wanted my square for the quilt to express what a sustainable urban ecology would look like with human beings and plants and animals coexisting in harmony in a city. Given the role that population density, public transportation, and greater access to education, jobs, and cultural engagement—museums, theater, galleries, and so on—can play in combating climate change, cities are crucial sites for mitigating the worst ecological crisis in human history. I considered various slogans: “Toward a Revolutionary Urban Ecology,” “The Right to the City,” and “Another World Is Possible.” But the actual design of the square dictated something less explicit, more metaphorical.

In designing the square, I placed blocks of fabric that drew my eye in a quilt-like pattern with two of the same pieces catacorner—blue fish in a sea and flowers on a turquoise background; in between are four wavy red rectangles, perhaps rays of light, in vertical and horizontal lines; and a yellow sun in the center. In the lower left hand corner, a woman is leaping, holding a flag; to her right is a blossoming tree; above the tree is a bird, wings spread; and in the center, enveloped by the sun, is the trace of a cityscape.

Instead of the slogans I had initially considered putting on the flag, I embroidered (a bit crudely) the word “stardust,” signifying the origins of life. The word started to mean more to me after reading the Marxist sociologist Erik Olin Wright’s public diary as he was dying from leukemia. He wrote about his time left “in this marvelous form of stardust,” observing that “Atoms don’t have experiences. They’re just stuff. That’s all I really am is stuff. But stuff so complexly organized across several thresholds of stuff-complexity, that it’s able to reflect upon its stuff-ness and what an extraordinary thing it has been to be alive and aware that it’s alive and aware that it’s aware that it’s alive. And from that complexity comes the love and beauty and meaning that constitutes the life I’ve lived.”

This deep knowledge of the stardust from which we came and to which we return in nonhuman form connects us to everything around us on earth and across the universe. But to realize that harmony between nature and humans will mean enacting a revolutionary urban ecology; demanding the right to the city; sustaining the natural world of which we are part and which global capitalism, run amok, is destroying; and making our own history to prove that another world is possible.

-

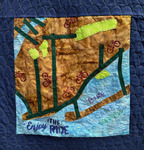

Enjoy the Ride

David Stoelting

I have been bicycling on the bridges, roads and parks of New York City for more than thirty years. During that time the experience of biking in New York has improved considerably through the creation of bike lanes in all parts of the city. The construction of bike lanes – especially protected bike lanes in which parked cars form a barrier between bikers and traffic – serve to reclaim the streets from the vehicles which dominate the roads. As my quilt block states, “bike lanes renew” the urban environment because they facilitate and prioritize human-powered, zero-emission transportation over gas-guzzling, exhaust-spewing motor vehicles.

Bikes lanes are a boon to the environment and are recognized as a critical component of the urban sustainability project. Bicycling reduces carbon dioxide emissions and noise pollution. Riding a bike also improves mental and physical health. And more bike lanes lead to more bicyclists on the roads, which in turn reduces the risks of bicycling.

My square depicts Brooklyn as well as parts of Manhattan and Queens. Prospect Park, Green-Wood Cemetery, Shirley Chisholm Park, and Forest Park are all shown, and the green strips represent prominent bikes lanes. These of course are not all of the bike lanes, only a representative sample. In recent months I have been thrilled to come across newly created two-way protected bike lanes along Schermerhorn Street and in Sheepshead Bay. And the NYC Department of Transportation is continuing to expand and fortify the network of bike lanes.

Creating this square required me to develop new skills. I had to learn how to sew, thread a needle, cut fabric, and embroider. My hope is that people seeing this who are not bikers will similarly be inspired to take up a new activity and discover the joys of pedaling around this diverse and ever-changing city of ours.

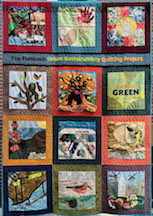

A collaborative Flatbush-Lefferts Gardens community discussion and creative project centered on urban sustainability issues: environmental justice, climate change, food access, and social inequality. Led by LIU Professor Deborah Mutnick, Humanities Department, and Margaret Marcy Emerson, Co-President, Brooklyn Quilters Guild. Generously supported by a Citizens Committee for New York City Neighborhood Grant.

Printing is not supported at the primary Gallery Thumbnail page. Please first navigate to a specific Image before printing.